import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

import jax.random as jr

from typing import *

K = 100

D = 30

Xi = jr.uniform(jr.PRNGKey(55), (K, D)) # Each row stores a random D-dimensional patternConditional Image Generation

\[ \DeclarePairedDelimiters{\set}{\left\{}{\right\}} \DeclareMathOperator*{\argmax}{argmax} \DeclareMathOperator*{\softmax}{softmax} \]

Hopfield Networks for the Modern Era of AI

Our brains are Associative Memories

Our brains have the ability to store and recall a lot of information across many different sensory modalities: e.g., vision, sound, smells, emotions, language, and movement. These events are highly interconnected – certain smells or sounds are linked with involuntary emotional responses, or perhaps elicit memories of formative events from our youth. This is the idea of Content Addressible Memory, where a complete memory – i.e., a collection of contemporaneous sensory inputs that are stored in the brain – can be retrieved by only a part of the full memory.

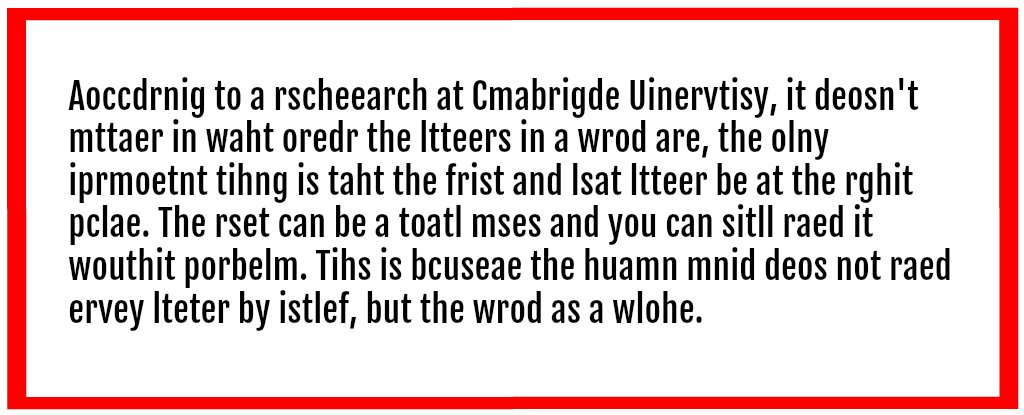

Similarly, our brains are quite robust to noisy signals, able to make sense of data that is complete gibberish. Consider the example shown in Figure 1 where the letters in each word are jumbled, and yet we can read the text with almost no latency or confusion. Thus, we can say that our brains are powerful Error Correctors: we can easily make sense of corrupted text that is close enough to the intended message.

The theory of Associative Memory compiles the above two behaviors into a single model, where both Content Addressible Memory and Error-Correction are encoded into a single attractor system whose dynamics are defined as gradient descent down an explicit Energy Function.

Associative Memories can be simultaneously understood as Content Addressible Memories, Error Correctors, and Energy Based Models.

Energy Based Models

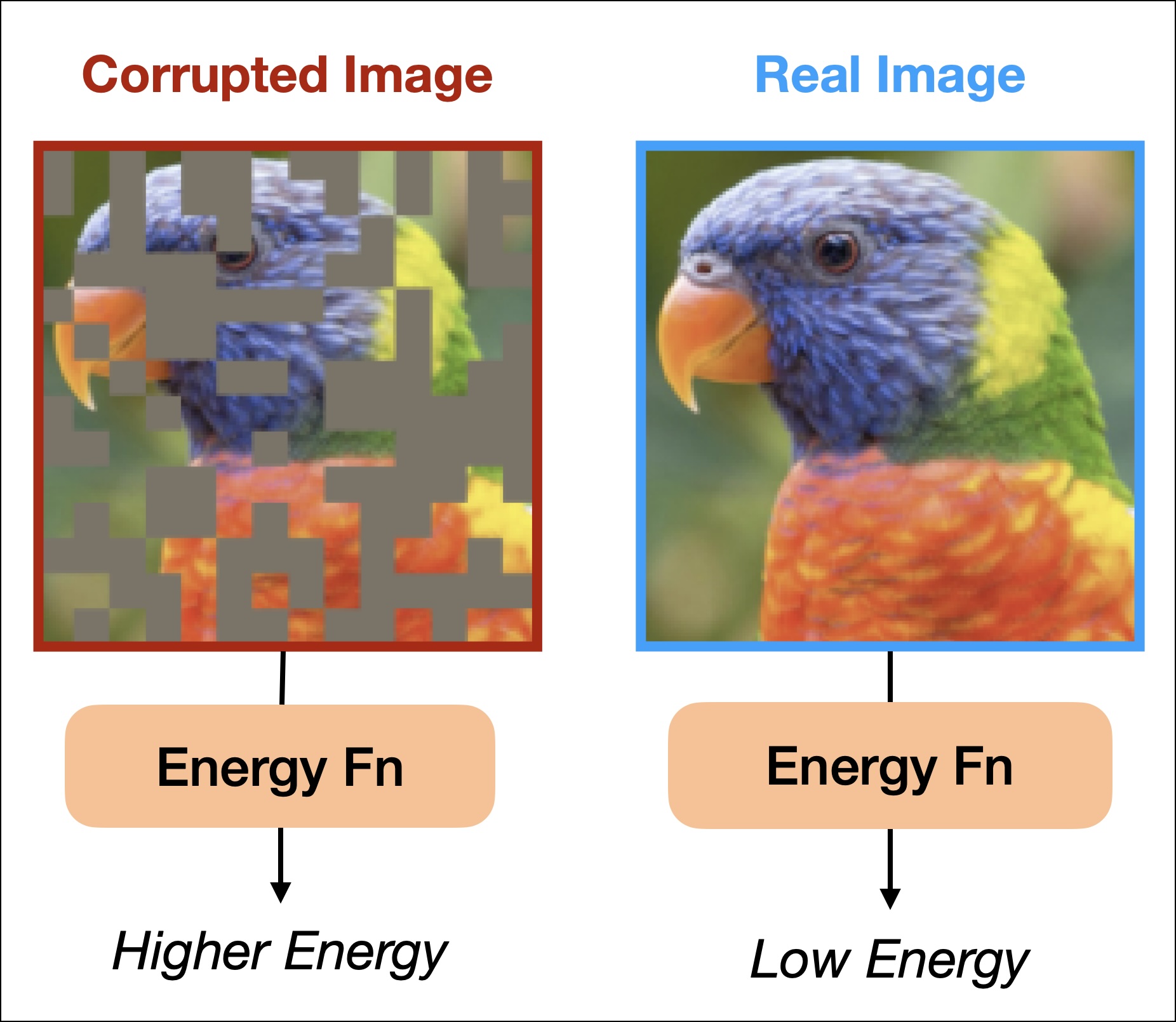

Energy has many physical interpretations, but in the context of machine learning it is helpful to view the energy function \(E_\theta\) as a proxy for the learned probability distribution \(P_\theta\) (using a model parameterized by \(\theta\)), as is formalized by the Boltzmann Distribution

\[ P_\theta(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{\exp(- \beta E_\theta(\mathbf{x}))}{Z_\theta}, \tag{1}\]

where \(\mathbf{x}\) represents a datapoint, \(\beta\) is an inverse temperature parameter controlling how “spiky” our distribution is, and \(Z_\theta\) is the partition function ensuring that \(P_\theta\) integrates to \(1\). The energy of a datapoint should be low to indicate that the data looks “real” – i.e., when the data looks like it was drawn from high-probability regions of the data distribution. In cases where the data looks corrupted, the energy will be high (see a simple illustration in Figure 2).

From Equation 1, we see that energy is equal to negative log-probability under some constant shift \(C := - \log Z_\theta\) ,

\[ E(\mathbf{x}) = - \frac{1}{\beta} \log (P_\theta (\mathbf{x})) + C. \]

It is also clear that the negative gradient of the energy is equal to the gradient of log-probability

\[ - \nabla_{\mathbf{x}} E = \frac{1}{\beta} \nabla_{\mathbf{x}} \log P_\theta, \tag{2}\]

which is the definition of the score function from Diffusion Modeling literature (Song and Ermon 2019).

So why should we prefer modeling the energy over the probability? Probability distributions are elegant to reason about and easy to sample from. However, it turns out that the partition function \(Z_\theta\) is intractable for any complex parameterizations for \(P_\theta\) (like we see everywhere in deep learning). Hence, most techniques prefer modeling either the score function (e.g., Diffusion Models (Song and Ermon 2019)) or the energy directly (e.g., the general class of EBMs (LeCun et al., n.d.)).

So you want to sample from your EBM

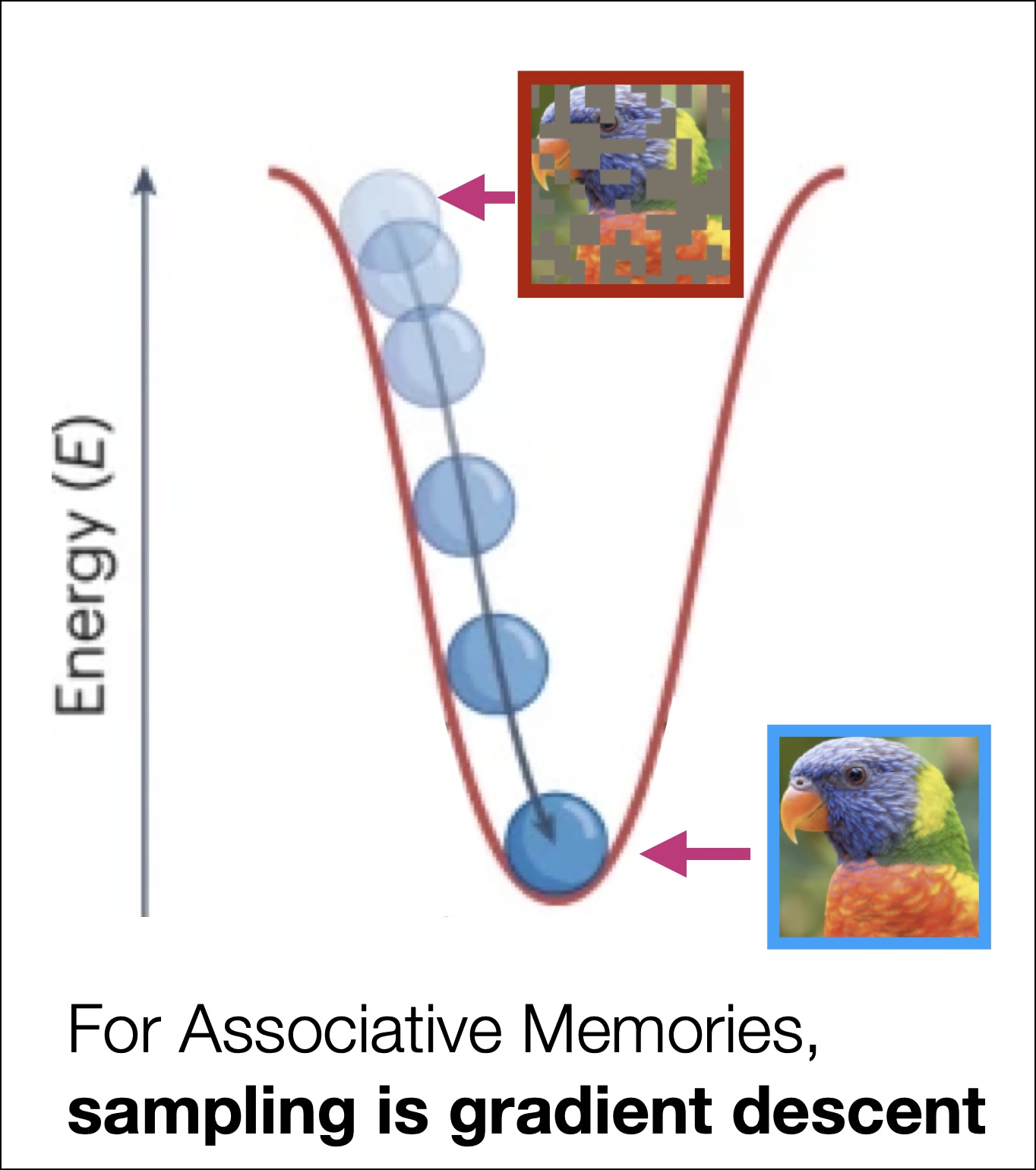

For reasons outside the scope of this tutorial, sampling from EBMs is hard.1 It would be a lot easier if we could just, say, try to minimize the energy (maximize the log-probability) of some initial noise by performing gradient descent on the energy (as hinted at in Equation 2).

However, there are several problems with this. Namely, a generic energy function \(E_\theta: \mathbb{R}^D \mapsto \mathbb{R}\) is any function that maps high dimensional data (say, in \(\mathbb{R}^D\)) to a scalar. There is no guarantee as to the underlying structure of the energy function: how do we know that an arbitrarily parameterized energy function is differentiable everywhere (i.e., that it is a smooth and continuous function)? If it were, then we could define a dynamical system to perform gradient descend down the energy of some initial corrupted sample (or even pure noise) to sample data from the original distribution

\[ \tau \frac{d\mathbf{x}}{dt} = - \nabla_{\mathbf{x}} E, \tag{3}\]

where \(\tau\) is a time constant that governs how quickly the state \(\mathbf{x}\) evolves and the goal is to minimize the energy (maximize the log-likelihood) that the sample comes from the original distribution, painting “inference as an optimization problem”. But if we do this, we would also like to ensure that the energy is bounded from below so that our dynamics will be guaranteed to converge (i.e., that our model is able to say, “STOP EVOLVING, I can’t descend the energy any further. This is the best I can do with the data and optimization strategy you’ve given me”) while \(\frac{dE}{dt} \leq 0\) for all time \(t\).

If the energy function is both (1) differentiable everywhere and (2) bounded from below, it is called by a special name: it is a Lyapunov energy function and thus, in the context of learning data distributions, an Associative Memory. Fixed points of the dynamics (occurring at points \({\mathbf{x}}^\star\) where \(\frac{d\mathbf{x}^\star}{dt} = 0\)) live at local minima of the energy function: we call these local minima memories. The sampling/inference in Equation 3 is the dynamic process of memory retrieval.

Associative Memories are Lyapunov energy functions where memories live at local energy minima, and inference is an optimization problem known as memory retrieval.

A Modern Perspective of the Classical Hopfield Network

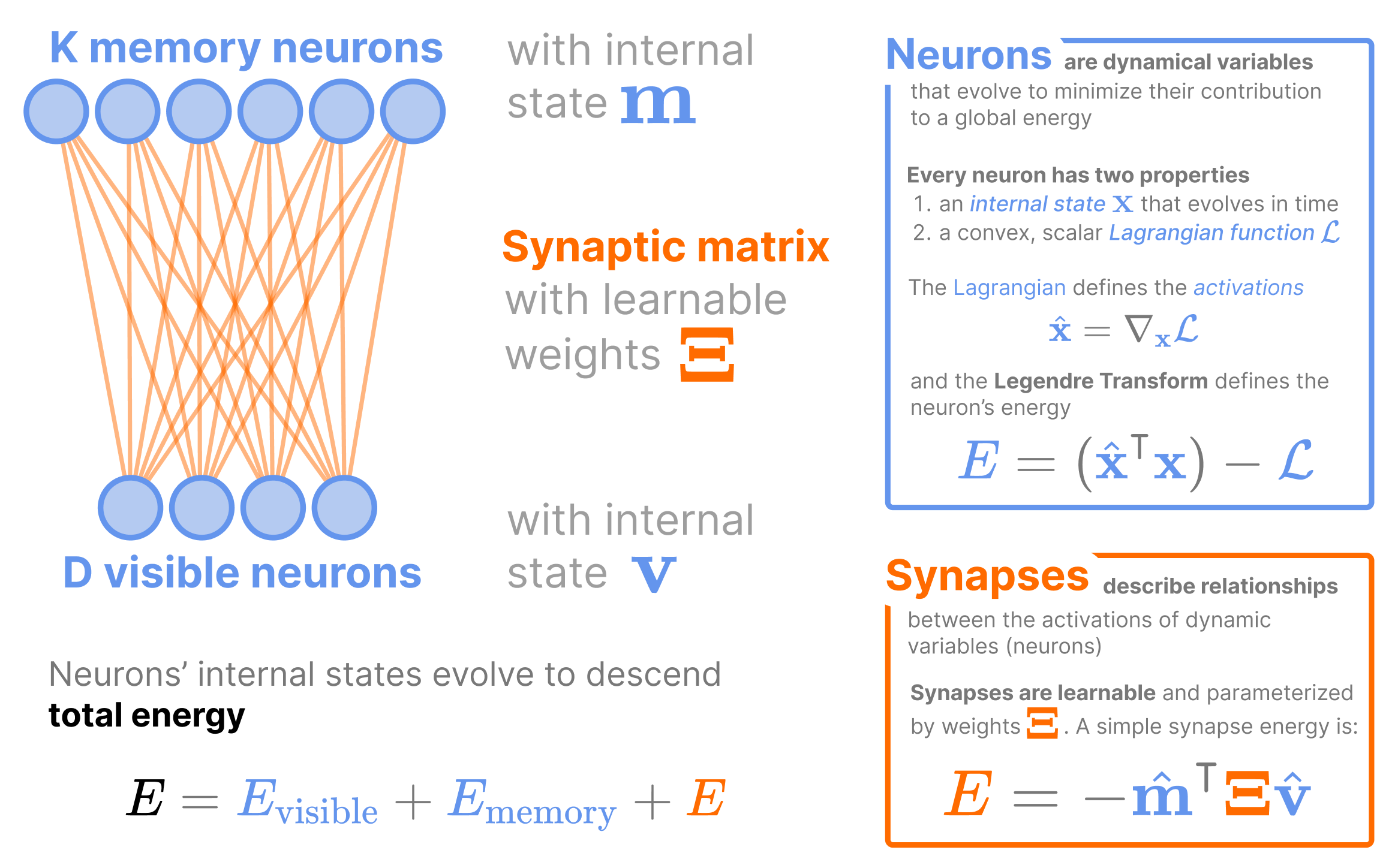

In the 1980s, John Hopfield formulated the very first energy-based model for Associative Memory in the Hopfield Network J. Hopfield (1984), which modeled how a collection of neurons and synapses could perform memory retrieval (we call this model the “Classical Hopfield Network” (CHN) to distinguish from modern variants). The CHN is the simplest of all Associative Memories, storing \(K\) patterns of dimension \(D\) in a single synaptic weight matrix (which we denote as the matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Xi}\in \mathbb{R}^{K \times D}\), the vector \(\boldsymbol{\xi}_\mu \in \mathbb{R}^{D}\) to represent pattern \(\mu\), and the scalar \(\xi_{\mu i}\) to indicate the \(i\)’th element of pattern \(\mu\)). The synaptic weights are the edges of a bipartite graph connecting the \(D\) visible neurons to \(K\) memory neurons (shown in Figure 4).

Let’s start to track things in code. We will use JAX for this tutorial, and we choose variable names that mirror the math.

We present the mathematics of the CHN with a modern formulation that uses Lagrangian functions to constrain the non-linear dynamics, as originally introduced in (Krotov and Hopfield 2021). Though at first this presentation may seem more complicated than traditional explanations of CHN dynamics, it is a powerful abstraction that lets us build hierarchical Associative Memories with complex parameterizations that resemble modern Deep Learning architectures. We demonstrate that we can build a modular, energy-based framework from scratch around these ideas (think torch.nn for Associative Memories) in (COMING SOON).

Neurons: A Tale of Two States

In Associative Memories, all dynamic variables have both an internal state and an axonal state (a non-linear function of the internal state). This terminology of internal/axonal is inspired by biology, where the internal state is analogous to the internal current of a neuron (other neurons don’t see the inside of other neurons) and the axonal state is analagous to a neuron’s firing rate (Associative Memories assume neurons communicate to other neurons via its firing rate). We denote the axonal state of a variable with a hat: i.e., dynamic variable (internal state) \(\mathbf{x}\) has axonal state \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}\), which is often some non-linear function of \(\mathbf{x}\). We call the axonal state \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}\) the activations of internal state \(\mathbf{x}\).

These two states are conjugate variables under the Legendre Transform of a Lagrangian function, much like velocity and momentum are conjugate variables of each other in classical mechanics. That is, given a convex Lagrangian function \(\mathcal{L}_{x}: \mathbb{R}^{D} \mapsto \mathbb{R}\) defined on the internal states \(\mathbf{x}\in \mathbb{R}^D\), the activations are defined as \(\hat{\mathbf{x}} := \nabla_{\mathbf{x}} \mathcal{L}_x\) and the neuron energy \(E_x\) is the value of the Legendre Transform

\[ E_x = \hat{\mathbf{x}}^\intercal \mathbf{x}- \mathcal{L}_x. \tag{4}\]

Let’s go ahead and prescribe Lagrangian functions to the neurons of the CHN on continuous states, which uses a sigmoid activation (with inverse temperature \(\beta = \frac{1}{2D}\)) on the visible units and an identity function on the memory units

\[ \begin{align*} \mathcal{L}_v &= 2D \sum\limits_{i=1}^D \log (\exp(\frac{v_i}{2D}) + 1)\\ \mathcal{L}_m &= \frac{1}{2} \sum\limits_{\mu=1}^K m_\mu^2, \end{align*} \]

and test that these Lagrangians behave as expected.

def quadratic_lagrangian(x):

"""The lagrangian of the identity function"""

return 0.5 * jnp.sum(x**2)

# We have to manually handle some numerical stability issues of the sigmoid in JAX

def sigmoid_lagrangian(x,

beta=1. # Amount to stretch the range of the sigmoid

):

"""The lagrangian of the sigmoid activation function"""

return _sigmoid_lagrangian(x, beta).sum()

@jax.custom_jvp

def _sigmoid_lagrangian(x, beta=1. ):

return 1 / beta * jnp.log(jnp.exp(beta * x) + 1)

@_sigmoid_lagrangian.defjvp

def _sigmoid_lagrangian_jvp(primals, tangents):

x, beta = primals

x_dot, beta_dot = tangents

primal_out = _sigmoid_lagrangian(x)

tangent_out = jax.nn.sigmoid(beta * x) * x_dot

return primal_out, tangent_out

vbeta = 1 / (2*D)

Lv_fn = lambda x: sigmoid_lagrangian(x, beta=vbeta) # The Lagrangian function of the visible neurons

Lm_fn = quadratic_lagrangian # The Lagrangian function of the memory neurons

vhat_fn = jax.grad(Lv_fn)

mhat_fn = jax.grad(Lm_fn)

# Test that the gradient of these Lagrangians matches our expected activation functions

v = jr.uniform(jr.PRNGKey(3), (D,))

m = jr.normal(jr.PRNGKey(4), (K,))

assert jnp.allclose(jax.nn.sigmoid(vbeta * v), vhat_fn(v))

assert jnp.allclose(m, mhat_fn(m))The energy of each layer is the Legendre Transform of the corresponding Lagrangian (Equation 4), which is easily implemented in JAX.

def legendre_transform(

F: Callable # The function to transform

):

"""Transform F(x) into the conjugate function Fhat(xhat, x) using the Legendre transform.

We assume that Fhat is a function of both xhat and x to prevent the need for an inverse function mapping xhat to x"""

def Fhat(xhat, x): return xhat @ x - F(x)

return Fhat

Ev_fn = legendre_transform(Lv_fn) # The energy of the visible neurons

Em_fn = legendre_transform(Lm_fn) # The energy of the memory neuronsSynapses: Similarity functions

Thankfully, synapses are much simpler to model than neurons, since synapses are energy functions that describe the alignment between 2 or more neurons. The simplest synaptic energy is that used by the CHN, where a single weight matrix parameterizes the dot-product alignment between the dynamic activations of the visible neurons (\(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\)) and the memory neurons (\(\hat{\mathbf{m}}\))

\[ E_S = - \hat{\mathbf{m}}^\intercal \boldsymbol{\Xi}\hat{\mathbf{v}}. \tag{5}\]

Let’s quickly implement this function before moving onto the interesting dynamics of this system.

def ES_fn(vhat, mhat, Xi):

"""The energy of the synapse"""

return -mhat.T @ (Xi @ vhat)Total energy and time evolution

We can add all the energies of the different components to get the total energy for the entire system

\[ E = E_v + E_m + E_S. \tag{6}\]

Memory retrieval is gradient descent down this total energy w.r.t. the activations of each neuron

\[ \begin{dcases} \tau \frac{d\mathbf{v}}{dt} &= - \nabla_{\hat{\mathbf{v}}} E\\ \tau \frac{d\mathbf{m}}{dt} &= - \nabla_{\hat{\mathbf{m}}} E. \end{dcases} \]

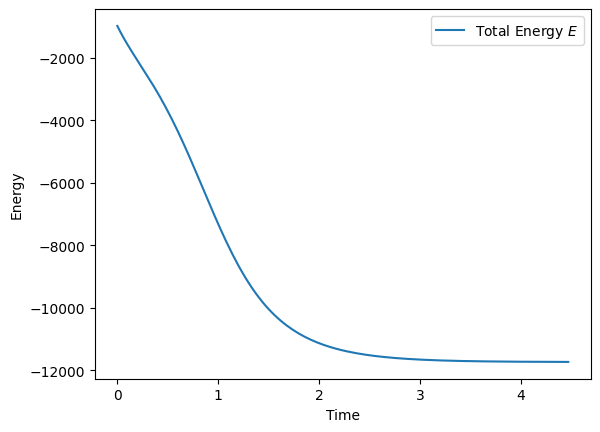

We have the power of JAX’s autograd at our disposal, so we’re done! Let’s test that the energy of our CHN converges.

def E_fn(vhat, mhat, v, m, Xi):

"""The total energy of the CHN"""

Ev = Ev_fn(vhat, v)

Em = Em_fn(mhat, m)

ES = ES_fn(vhat, mhat, Xi)

E = Ev + Em + ES

return E, (Ev, Em, ES) # Return other energies for plotting, if desired

dE_dvhat_fn = jax.value_and_grad(E_fn, argnums=0, has_aux=True) # The gradient of the energy w.r.t. the visible neurons

dE_dmhat_fn = jax.value_and_grad(E_fn, argnums=1, has_aux=True) # The gradient of the energy w.r.t. the memory neurons

v = jr.uniform(jr.PRNGKey(3), (D,))

m = jr.normal(jr.PRNGKey(4), (K,))

alpha = 0.03 # Step down gradient. Like "Learning rate"

all_E = []

for i in range(150):

vhat = vhat_fn(v)

mhat = mhat_fn(m)

(E, aux), dE_dvhat = dE_dvhat_fn(vhat, mhat, v, m, Xi)

_, dE_dmhat = dE_dmhat_fn(vhat, mhat, v, m, Xi)

v = v - alpha * dE_dvhat

m = m - alpha * dE_dmhat

all_E.append(E)

We have chosen strictly convex Lagrangian functions, which means that the Hessian of our Lagrangians is positive definite everywhere (i.e., \(\frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{x}^2} > 0\)). Thus, energy of the whole system is guaranteed to decrease over time (\(\frac{dE}{dt} \leq 0\), see proof in Appendix of (Krotov and Hopfield 2021)).

Solving the Storage Capacity with Dense Associative Memories

We have successfully built a continuous version of the CHN. Unfortunately, the model that we just implemented suffers from incredibly low memory storage capacity. Thankfully, all we have to do to increase the storage capacity is choose a different Lagrangian function on our memory neurons. Doing this is the key to creating Dense Associative Memories (Krotov and Hopfield 2016).

Specifically, let’s use the logsumexp Lagrangian function proposed by (Ramsauer et al. 2022)

\[ \mathcal{L}_m = \frac{1}{\beta} \log \sum\limits_{\mu=1}^K \exp(\beta m_\mu) \]

whose activation function is the popular softmax

\[ \hat{m}_\mu = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}_m}{\partial m_\mu} = \frac{\exp(\beta m_\mu)}{\sum\limits_{\nu = 1}^K \exp(\beta m_\nu)}. \]

For this, let’s just choose \(\beta=1.\).

def lagr_softmax(x, beta: float = 1.0):

return 1 / beta * jax.nn.logsumexp(beta * x, axis=-1, keepdims=False)

mbeta = 1.

Lm_fn = lambda m: lagr_softmax(m, beta=mbeta) # The NEW Lagrangian function of the memory neurons

mhat_fn = jax.grad(Lm_fn)

# Test that the gradient of this Lagrangians matches our expected softmax

m = jr.normal(jr.PRNGKey(4), (K,))

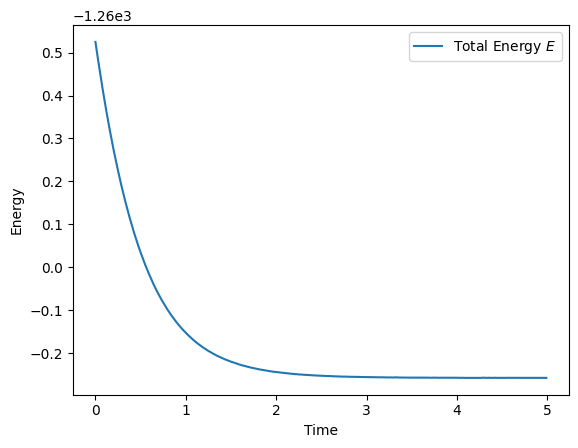

assert jnp.allclose(jax.nn.softmax(mbeta * m), mhat_fn(m))We have to duplicate a little code from before to rerun our energy descent plot, but just like that we have created Dense Associatve Memory: a version of the Hopfield Network with exponential storage capacity.

Em_fn = legendre_transform(Lm_fn) # Redefine the energy of the memory neurons

def E_fn(vhat, mhat, v, m, Xi):

"""The total energy of the DAM"""

Ev = Ev_fn(vhat, v)

Em = Em_fn(mhat, m)

ES = ES_fn(vhat, mhat, Xi)

E = Ev + Em + ES

return E, (Ev, Em, ES) # Return other energies for plotting, if desired

dE_dvhat_fn = jax.value_and_grad(E_fn, argnums=0, has_aux=True) # The gradient of the energy w.r.t. the visible neurons

dE_dmhat_fn = jax.value_and_grad(E_fn, argnums=1, has_aux=True) # The gradient of the energy w.r.t. the memory neurons

v = jr.uniform(jr.PRNGKey(3), (D,))

m = jr.normal(jr.PRNGKey(4), (K,))

alpha = 0.01 # Step down gradient. Like "Learning rate"

all_E = []

for i in range(500):

vhat = vhat_fn(v)

mhat = mhat_fn(m)

(E, aux), dE_dvhat = dE_dvhat_fn(vhat, mhat, v, m, Xi)

_, dE_dmhat = dE_dmhat_fn(vhat, mhat, v, m, Xi)

v = v - alpha * dE_dvhat

m = m - alpha * dE_dmhat

all_E.append(E)

Gee all this code duplication for such a simple change. Wouldn’t it be nice to implement a Lagrangian-based framework around these abstractions? Doing this from scratch in \({<}200\) lines of code will be an accompanying post to this tutorial.

Energy bounds are nice, but do these models work?

Quick recap:

Hopfield Networks are associative memories concerned with the storage and retrieval of data using a Lyapunov Function (“energy function”). A Hopfield Network’s memories are stored at local minima of this energy function. Given an initial data point, Hopfield Networks retrieve memories (perform “inference”) by explicitly descending the energy (following the negative gradient of the energy). This inference process is a dynamical system that is guaranteed to converge to the fixed points (“memories”)

We have built a Hopfield Network (specifically, a Dense Associative Memory) demo that runs live in your web browser. The data stored in the network are the headshots of each person responsible for putting together the AMHN Workshop @NeurIPS 2023. The animation below has two states:

- the selected person (the “label”)

- the currently displayed image (the “dynamic state”)

At every step, we display the recent history of energy values as a lineplot alongside a 2-D PCA projection of the current dynamic state (image). Watch as the dynamic state moves around the energy landscape characterized by local minima at each person!

The animation runs continously (changing the selected person every 6 seconds), taking small steps down the predicted energy of each (label, dynamic_state) pair. If it looks like the animation stops running when the picture is clear, it is only because we have reached the appropriate local minimum of the energy: the model is still subtracting the energy gradient from the image (it so happens that the energy gradient is zero when the dynamic state equals the original headshot).

See the description below for a more technical description.

The Anatomy of our Hopfield Network

An Associative Memory is a dynamical system that is concerned with the memorization and retrieval of data.

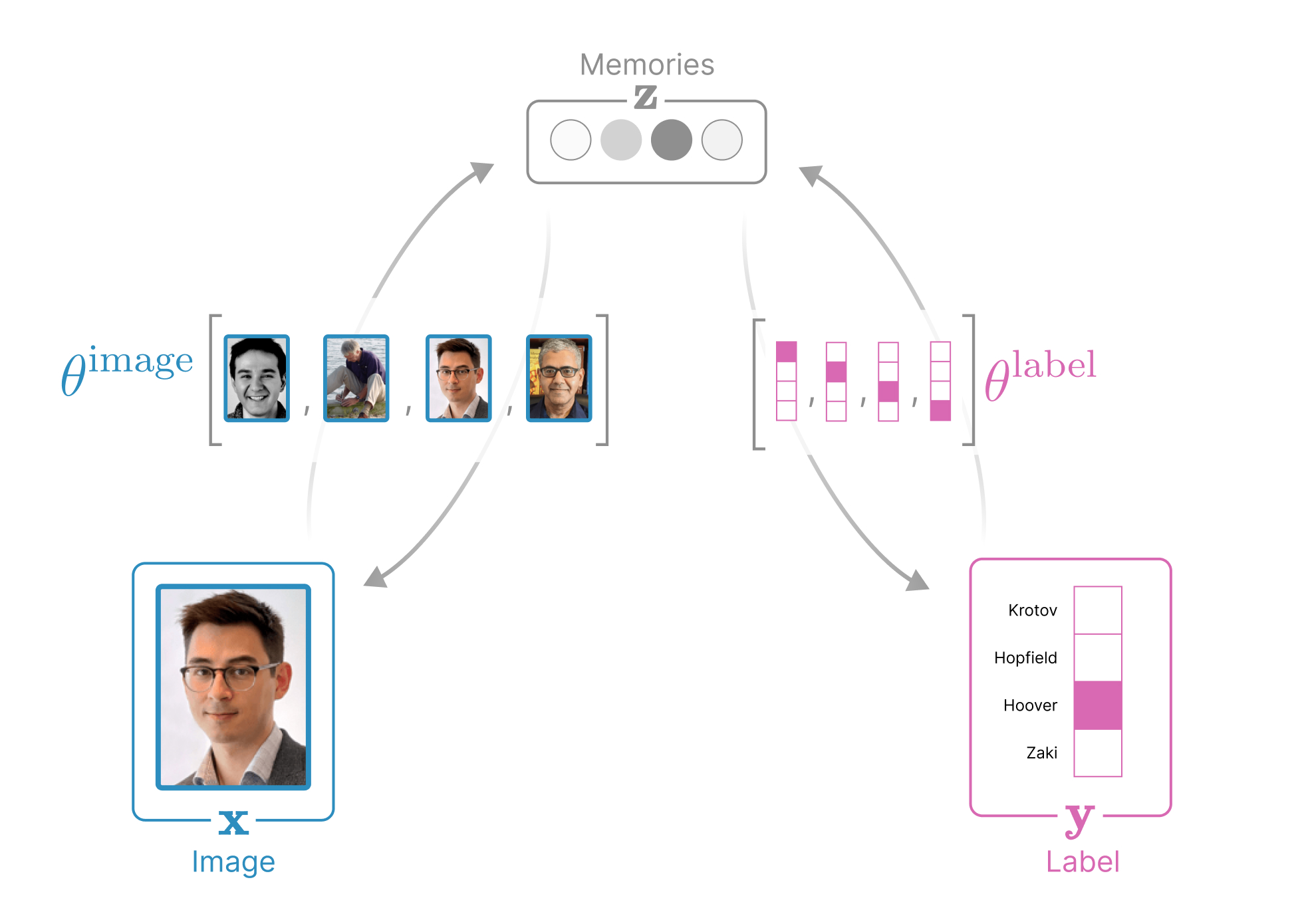

The structure of our data in the demo above is a collection of (image, label) pairs, where each image variable \(x \in \mathbb{R}^{3N_\text{pixels}}\) is represented as a rasterized vector of the RGB pixels and each label variable \(y \in \mathbb{R}^{N_\text{people}}\) identifies a person and is represented as a one-hot vector. Our Associative Memory additionally introduces a third, hidden variable for the memories \(z \in \mathbb{R}^{N_\text{memories}}\). These three variables are connected to each other via synapses (relationships).

In Associative Memories, each of these variables has both an internal state that evolves in time and an axonal state (an isomorphic function of the internal state that represents its conjugate variable under the Legendre Transform) that influences how the rest of the network evolves. This terminology of internal/axonal is inspired by biology, where the “internal” state is analogous to the internal current of a neuron (other neurons don’t see the inside of other neurons) and the “axonal” state is analagous to a neuron’s firing rate (we assume a neuron communicates to other neurons via its firing rate). We denote the axonal state of a variable with a hat: (i.e., variable \(x\) has axonal state \(\hat{x}\), \(y\) has axonal state \(\hat{y}\), and \(z\) has axonal state \(\hat{z}\))

Dynamic variables in Associative Memories have two states: an internal state and an axonal state.

We call the axonal state the *activations and they are uniquely defined by our choice of a scalar and convex Lagrangian function on that variable (Krotov 2021; Krotov and Hopfield 2021; Hoover et al. 2022). Specifically, in this demo we choose

\[ \begin{align*} L_x(x) &:= \frac{1}{2} \sum\limits_i x_i^2\\ L_y(y) &:= \log \sum\limits_k \exp (y_k)\\ L_z(z) &:= \frac{1}{\beta} \log \sum\limits_\mu \exp(\beta z_\mu) \end{align*} \]

These Lagrangians dictate the axonal states (activations) of each variable.

\[ \begin{align*} \hat{x} &= \nabla_{x} L_x = x\\ \hat{y} &= \nabla_{y} L_y = \softmax(y)\\ \hat{z} &= \nabla_{z} L_z = \softmax(\beta z) \end{align*} \]

The Legendre Transform of the Lagrangian defines the energy of each variable.

\[ \begin{align*} E_x &= \sum\limits_i \hat{x}_i x_i - L_x\\ E_y &= \sum\limits_k \hat{y}_k y_k - L_y\\ E_z &= \sum\limits_\mu \hat{z}_\mu z_\mu - L_z\\ \end{align*} \]

All variables in Associative Memories have a special Lagrangian function that defines the axonal state and the energy of that variable.

In the above equations, \(\beta > 0\) is an inverse temperature that controls the “spikiness” of the energy function around each memory (the spikier the energy landscape, the more memories can be stored). Each of these three variables is dynamic (evolves in time). The convexity of the Lagrangians ensures that the dynamics of our network will converge to a fixed point.

How each variable evolves is dictated by that variable’s contribution to the global energy function \(E_\theta(x,y,z)\) (parameterized by weights \(\theta\)) that is LOW when the image \(x\), the label \(y\), and the memories \(z\) are aligned (look like real data) and HIGH everywhere else (thus, our energy function places real-looking data at local energy minima). In this demo we choose an energy function that allows us to manually insert memories (the (image,label) pairs we want to show) into the weights \(\theta = \set{\theta^\text{image} \in \mathbb{R}^{N_\text{memories} \times 3N_\text{pixels}},\; \theta^\text{label} \in \mathbb{R}^{N_\text{memories} \times N_\text{people}}}\). As before, let \(\mu = \set{1,\ldots,N_\text{memories}}\), \(i = \set{1,\ldots,3N_\text{pixels}}\), and \(k = \set{1,\ldots,N_\text{people}}\). The global energy function in this demo is

\[ \begin{align} E_\theta &= E_x + E_y + E_z + \frac{1}{2} \left[ \sum\limits_\mu \hat{z}_\mu (\sum\limits_i \theta^\mathrm{image}_{\mu i} - \hat{x}_i)^2 - \sum\limits_i \hat{x}_i^2\right] - \lambda \sum\limits_{\mu} \sum\limits_k \hat{z}_\mu \theta^\mathrm{label}_{\mu k} \hat{y}_k\\ % E_\theta &= E_x + E_y + E_z + \frac{1}{2} \sum\limits_\mu \hat{z}_\mu (\sum\limits_i \theta^\mathrm{image}_{\mu i} - \hat{x}_i)^2 - \lambda \sum\limits_{\mu} \sum\limits_k \hat{z}_\mu \theta^\mathrm{label}_{\mu k} \hat{y}_k\\ &= E_x + E_y + E_z + E_{xz} + E_{yz} \end{align} \]

The second term of \(E_{xz}\) removes \(E_x\) from the total energy ONLY because we chose to use L2 similarities rather than dot products. For pedagogical purposes, you can safely ignore the second term in \(E_{xz}\).

We introduce \(\lambda > 1\) to encourage the dynamics to align with the label.

Associative Memories can always be visualized as an undirected graph.

Every associative memory can be understood as an undirected graph where nodes represent dynamic variables and edges capture the (often learnable) alignment between dynamic variables. Notice that there are five energy terms in this global energy function: one for each node (\(E_x\), \(E_y\), \(E_z\))), and one for each edge (\(E_{xz}\) captures the alignment between memories and our image and \(E_{yz}\) captures the alignment between memories and our label). See Figure 5 for the anatomy of this network.

This global energy function \(E_\theta(x,y,z)\) turns our images \(x\), labels \(y\), and memories \(z\) into dynamic variables whose internal states evolve according to the following differential equations:

\[ \begin{align*} \tau_x \frac{dx_i}{dt} &= -\frac{\partial E_\theta}{\partial \hat{x}_i} = \sum\limits_\mu \hat{z}_\mu \left( \theta^\mathrm{image}_{\mu i} - \hat{x}_i \right)\\ \tau_y \frac{dy_k}{dt} &= -\frac{\partial E_\theta}{\partial \hat{y}_k} = \lambda \sum\limits_\mu \hat{z}_\mu \theta^\mathrm{label}_{\mu k} - \hat{y}_k\\ \tau_z \frac{dz_\mu}{dt} &= -\frac{\partial E_\theta}{\partial \hat{z}_\mu} = - \frac{1}{2} \sum\limits_i \left(\theta^\mathrm{image}_{\mu i} - \hat{x}_i \right)^2 + \lambda \sum\limits_k \theta^\mathrm{label}_{\mu k} \hat{y}_k - \hat{z}_\mu\\ \end{align*} \]

where \(\tau_x, \tau_y, \tau_z\) define how quickly the states evolve.

The variables in Associative Memories always seek to minimize their contribution to a global energy function.

Note that in the demo we treat our network as an image generator by clamping the labels (i.e., forcing \(\frac{d\hat{y}}{dt} = 0\)). We can similarly use the same Associative Memory as a classifier by clamping the image (forcing \(\frac{d\hat{x}}{dt} = 0\)) and allowing only the label to evolve.

The Code

The model for the above javascript demo was created using the following JAX code.

References

Footnotes

An excellent introduction to why sampling EBMs is hard can be found in Stefano Ermon’s lecture slides.↩︎